Mortgage-backed security

| Securities | |

|

|

|

Securities |

|

|

Markets |

|

|

Bonds by coupon |

|

|

Bonds by issuer |

|

|

Equities (stocks) |

|

|

Investment funds |

|

|

Structured finance Tranche Credit-linked note |

|

|

Derivatives |

|

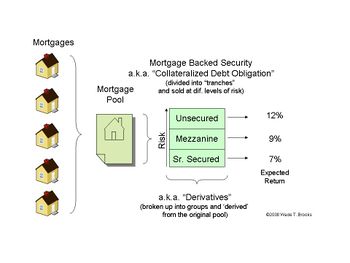

A mortgage-backed security (MBS) is an asset-backed security or debt obligation that represents a claim on the cash flows from mortgage loans through a process known as securitization.

Contents |

Overview

First, mortgage loans are purchased from banks, mortgage companies, and other originators. Then, these loans are assembled into pools. This is done by government agencies, government-sponsored enterprises, and private entities, which may offer features to mitigate the risk of default associated with these mortgages. These securities are usually sold as bonds, but financial innovation has created a variety of securities that derive their ultimate value from mortgage pools.

In the United States, most MBS's are issued by the Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) and the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac), U.S. government-sponsored enterprises. Ginnie Mae, backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government, guarantees that investors receive timely payments. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac also provide certain guarantees and, while not backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government, have special authority to borrow from the U.S. Treasury. Some private institutions, such as brokerage firms, banks, and homebuilders, also securitize mortgages, known as "private-label" mortgage securities. Today, all three organizations actively repackage and sell mortgages as pass-throughs. Ginnie Mae guarantees timely payment of principal and interest on its pass-throughs. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac guarantee payment of principal and interest.[1][2]

Residential mortgages in the United States have the option to pay more than the required monthly payment (curtailment) or to pay off the loan in its entirety (prepayment). Because curtailment and prepayment affect the remaining loan principal, the monthly cash flow of an MBS is not known in advance, and therefore presents an additional risk to MBS investors.

Commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS) are secured by commercial and multifamily properties (such as apartment buildings, retail or office properties, hotels, schools, industrial properties and other commercial sites). The properties of these loans vary, with longer-term loans (5 years or longer) often being at fixed interest rates and having restrictions on prepayment, while shorter-term loans (1–3 years) are usually at variable rates and freely pre-payable.

History

Background

After the Great Depression, the federal government of the United States created the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) in the National Housing Act of 1934 to assist in the construction, acquirement, and/or rehabilitation of residential properties.[3] The FHA helped develop and standardize the fixed rate mortgage that is prevalent today as an alternative to the only other mortgage at the time, the balloon payment mortgage, and helped the mortgage design garner investors by insuring them.[4]

In 1938, the government also created the government-sponsored corporation Federal National Mortgage Association (FNMA), colloquially known as Fannie Mae, to create a liquid secondary market in these mortgages and thereby free the loan originators to originate more loans, primarily by buying FHA-insured mortgages.[5] In 1968 Fannie Mae was split into the current Fannie Mae and the Government National Mortgage Association (GNMA), colloquially known as Ginnie Mae, to support the FHA-insured mortgages, as well as Veterans Administration (VA) and Farmers Home Administration (FmHA) insured mortgages, with the full faith and credit of the United States government.[6] In 1970, the federal government authorized Fannie Mae to purchase private mortgages, i.e. those not insured by the FHA, VA, or FmHA, and created the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (FHLMC), colloquially known as Freddie Mac, to do much the same thing as Fannie Mae.[6] Ginnie Mae does not invest in private mortgages.

Securitization

Ginnie Mae guarenteed the first mortgage passthrough security of an approved lender in 1968.[7] In 1971 Freddie Mac issued its first mortgage passthrough, called a participation certificate, composed primarily of private mortgages.[7] In 1981 Fannie Mae issue its first mortgage passthrough and called it a mortgage-backed security.[8] In 1983 Freddie Mac issued the first collateralized mortgage obligation.[9]

In 1960 the government enacted the Real Estate Investment Trust Act of 1960 to allow the creation of the real estate investment trust (REIT) to encourage real estate investment. In 1977 Bank of America issued the first private label passthrough,[10] and in 1984 the government passed the Secondary Mortgage Market Enhancement Act (SMMEA) to improve the marketability of such securities.[10] The Tax Reform Act of 1986 allowed the creation of the tax-free Real Estate Mortgage Investment Conduit (REMIC) special purpose vehicle for the express purpose of issuing passthroughs.[11] The Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery and Enforcement Act of 1989 (FIRREA) dramatically changed the savings and loan industry and its federal regulation.[12] The Small Business Job Protection Act of 1996 introduced the Financial Asset Securitization Investment Trust (FASIT) that is similar to the REMIC but is able to securitize a wider array of assets.

Types

Most bonds backed by mortgages are classified as an MBS. This can be confusing, because some securities derived from MBS are also called MBS(s). To distinguish the basic MBS bond from other mortgage-backed instruments the qualifier pass-through is used, in the same way that "vanilla" designates an option with no special features.

Mortgage-backed security sub-types include:

- Pass-through mortgage-backed security is the simplest MBS, as described in the sections above. Essentially, a securitization of the mortgage payments to the mortgage originators. These can be subdivided into:

- Residential mortgage-backed security (RMBS) - a pass-through MBS backed by mortgages on residential property

- Commercial mortgage-backed security (CMBS) - a pass-through MBS backed by mortgages on commercial property

- Collateralized mortgage obligation (CMO) - a more complex MBS in which the mortgages are ordered into tranches by some quality (such as repayment time), with each tranche sold as a separate security.[13]

- Stripped mortgage-backed securities (SMBS): Each mortgage payment is partly used to pay down the loan's principal and partly used to pay the interest on it. These two components can be separated to create SMBS's, of which there are two subtypes:

- Interest-only stripped mortgage-backed securities (IO) - a bond with cash flows backed by the interest component of property owner's mortgage payments.

- Net interest margin securities (NIMS) - resecuritized residual interest of a mortgage-backed security[14]

- Principal-only stripped mortgage-backed securities (PO) - a bond with cash flows backed by the principal repayment component of property owner's mortgage payments.

- Interest-only stripped mortgage-backed securities (IO) - a bond with cash flows backed by the interest component of property owner's mortgage payments.

Varieties of underlying mortgages in the pool:

- Prime: conforming mortgages: prime borrowers, full documentation (such as verification of income and assets), strong credit scores, etc.

- Alt-A: an ill-defined category, generally prime borrowers but non-conforming in some way, often lower documentation (or in some other way: vacation home, etc.) (Article on Alt-A)

- Subprime: weaker credit scores, no verification of income or assets, etc.

There are also jumbo mortgages, when the size is bigger than the "conforming loan amount" as set by Fannie Mae.

These types are not limited to Mortgage Backed Securities. Bonds backed by mortgages, but are not MBS can also have these subtypes.

Covered bonds

In Europe there exists a type of asset-backed bond called a "covered bond" (commonly known by the German term Pfandbriefe). Pfandbriefe were first created in 19th century Germany when Frankfurter Hypo began issuing mortgage covered bonds. The market has been regulated since the creation of a law governing the securities in Germany in 1900. The key difference between Pfandbriefe and mortgage-backed or asset-backed securities is that banks that make loans and package them into Pfandbriefe keep those loans on their books. This means that when a company with mortgage assets on its books issue the covered bond its balance sheet grows, which it wouldn't do if it issued an MBS, although it may still guarantee the securities payments.

Market size and liquidity

There is about $14.2 trillion in total U.S. mortgage debt outstanding.[15] There are about $8.9 trillion in total U.S. mortgage-related securities.[16] The volume of pooled mortgages stands at about $7.5 trillion. About $5 trillion of that is securitized or guaranteed by government sponsored enterprises (GSEs) or government agencies, the remaining $2.5 trillion pooled by private mortgage conduits.[15] Mortgage backed securities can be considered to have been in the tens of trillions, if Credit Default Swaps are taken into account.

According to the Bond Market Association, gross U.S. issuance of agency MBS was:

- 2005: USD 0.967 trillion

- 2004: USD 1.019 trillion

- 2003: USD 2.131 trillion

- 2002: USD 1.444 trillion

- 2001: USD 1.093 trillion

Structure and features

Weighted-average maturity

The weighted-average maturity (WAM) of an MBS is the average of the maturities of the mortgages in the pool, weighted by their balances at the issue of the MBS. Note that this is an average across mortgages, as distinct from concepts such as weighted-average life and duration, which are averages across payments of a single loan.

To illustrate the concept of WAM, let's consider a mortgage pool with just three mortgage loans that have the below mentioned outstanding mortgage balances, mortgage rates, and months remaining to maturity.

| Loan | Outstanding Mortgage Balance | Mortgage Rate | Remaining Months to Maturity | Each Loan's Weighting |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loan 1 | $200,000 | 6.00% | 300 | 22.22% |

| Loan 2 | $400,000 | 6.25% | 260 | 44.44% |

| Loan 3 | $300,000 | 6.50% | 280 | 33.33% |

The weightings are computed by dividing each outstanding loan amount by total amount outstanding in the mortgage pool (i.e., $900,000). These amounts are the outstanding amounts at the issuance/initiation of the MBS. Now, the WAM for the above mortgage pool that consists of three loans is computed as follows:

WAM = 22.22% (300) + 44.44% (260) + 33.33% (280)

= 66.67 + 115.56 + 93.33

= 275.56 Months or 276 months after rounding

Weighted-average coupon

The weighted average coupon (WAC) of an MBS is the average of the coupons of the mortgages in the pool, weighted by their original balances at the issuance of the MBS. For the above example this is:

WAC = 22.22% (6.00) + 44.44% (6.25) + 33.33% (6.50)

= 1.333 + 2.778 + 2.167

= 6.28% after rounding

Why and where we use WAM and WAC

WAM and WAC are used for describing a mortgage passthrough security, and they form the basis for the computation of cash flows from that mortgage passthrough. Just as we describe a bond by saying 30 year bond with 6% coupon, we describe a mortgage passthrough by saying, for example, "this is a $3 billion passthrough with 6% passthrough rate, 6.5% WAC, and 340 month WAM."

Note here, the passthrough rate is different from WAC. The passthrough rate is the rate that the investor would receive if he/she holds this mortgage passthrough security (or simply mortgage passthrough). Almost always, the passthrough rate is less than the WAC. The difference goes to servicing (i.e., costs incurred in collecting the loan payments and transferring the payments to the investors) the mortgage loans in the pool.

Uses

There are many reasons for mortgage originators to finance their activities by issuing mortgage-backed securities. Mortgage-backed securities

- transform relatively illiquid, individual financial assets into liquid and tradable capital market instruments.

- allow mortgage originators to replenish their funds, which can then be used for additional origination activities.

- can be used by Wall Street banks to monetize the credit spread between the origination of an underlying mortgage (private market transaction) and the yield demanded by bond investors through bond issuance (typically, a public market transaction).

- are frequently a more efficient and lower cost source of financing in comparison with other bank and capital markets financing alternatives.

- allow issuers to diversify their financing sources, by offering alternatives to more traditional forms of debt and equity financing.

- allow issuers to remove assets from their balance sheet, which can help to improve various financial ratios, utilise capital more efficiently and achieve compliance with risk-based capital standards.

The high liquidity of most mortgage-backed securities means that an investor wishing to take a position need not deal with the difficulties of theoretical pricing described below; the price of any bond is essentially quoted at fair value, with a very narrow bid/offer spread.

Reasons (other than investment or speculation) for entering the market include the desire to hedge against a drop in prepayment rates (a critical business risk for any company specializing in refinancing).

Pricing

Theoretical pricing

Pricing a vanilla corporate bond is based on two sources of uncertainty: default risk (credit risk) and interest rate (IR) exposure[17]. The MBS adds a third risk: early redemption (prepayment). The number of homeowners in residential MBS securitizations who prepay goes up when interest rates go down. One reason for this phenomenon is that homeowners can refinance at a lower fixed interest rate. Commercial MBS often mitigate this risk using call protection.

Since these two sources of risk (IR and prepayment) are linked, solving mathematical models of MBS value is a difficult problem in finance. The level of difficulty rises with the complexity of the IR model, and the sophistication of the prepayment IR dependence, to the point that no closed form solution (i.e. one you could write it down) is widely known. In models of this type numerical methods provide approximate theoretical prices. These are also required in most models which specify the credit risk as a stochastic function with an IR correlation. Practitioners typically use Monte Carlo method or Binomial Tree numerical solutions.

Interest rate risk and prepayment risk

Theoretical pricing models must take into account the link between interest rates and loan prepayment speed. Mortgage prepayments are most often made because a home is sold or because the homeowner is refinancing to a new mortgage, presumably with a lower rate or shorter term. Prepayment is classified as a risk for the MBS investor despite the fact that they receive the money, because it tends to occur when floating rates drop and the fixed income of the bond would be more valuable (negative convexity). Hence the term: prepayment risk

To compensate investors for the prepayment risk associated with these bonds, they trade at a spread to government bonds.

There are other drivers of the prepayment function (or prepayment risk), independent of the interest rate, for instance:

- Economic growth, which is correlated with increased turnover in the housing market

- Home prices inflation

- Unemployment

- Regulatory risk; if borrowing requirements or tax laws in a country change this can change the market profoundly.

- Demographic trends, and a shifting risk aversion profile, which can make fixed rate mortgages relatively more or less attractive.

Credit risk

The credit risk of mortgage-backed securities depends on the likelihood of the borrower paying the promised cash flows (principal and interest) on time. The credit rating of MBS is fairly high because:

- Most mortgage originations include research on the mortgage borrower's ability to repay, and will try to lend only to the credit-worthy. An important exception to this would be "no-doc" or "low-doc" loans.

- Some MBS issuers, such as Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae, guarantee against homeowner default risk. In the case of Ginnie Mae, this guarantee is backed with the full faith and credit of the US Federal government. This is not the case with Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac, but these two entities have lines of credit with the US Federal government; however, these lines of credit are extremely small when compared with the average amount of money circulated through Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac in one day's business. Additionally, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac generally require private mortgage insurance on loans in which the borrower provides a down payment that is less than 20% of the property value.

- Pooling many mortgages with uncorrelated default probabilities creates a bond with a much lower probability of total default, in which no homeowners are able to make their payments (see Copula). Although the risk neutral credit spread is theoretically identical between a mortgage ensemble and the average mortgage within it, the chance of catastrophic loss is reduced.

- If the property owner should default, the property remains as collateral. Although real estate prices can move below the value of the original loan, this increases the solidity of the payment guarantees and deters borrower default.

If the MBS was not underwritten by the original real estate & the issuer's guarantee the rating of the bonds would be very much lower. Part of the reason is the expected adverse selection against borrowers with improving credit (from MBSs pooled by initial credit quality) who would have an incentive to refinance (ultimately joining an MBS pool with a higher credit rating).

Real-world pricing

Most traders and money managers use Bloomberg and Intex to analyze MBS pools. Intex is also used to analyze more esoteric products. Some institutions have also developed their own proprietary software. TradeWeb is used by the largest bond dealers ("primaries") to transact round lots ($1 million+).

For "vanilla" or "generic" 30-year pools (FN/FG/GN) with coupons of 3.5% - 7%, one can see the prices posted on a TradeWeb screen by the primaries called To Be Announced (TBA). This is due to the actual pools not being shown. These are forward prices for the next 3 delivery months since pools haven't been cut — only the issuing agency, coupon and dollar amount are revealed. A specific pool whose characteristics are known would usually trade "TBA plus {x} ticks" or a "pay-up" depending on characteristics. These are called "specified pools" since the buyer specifies the pool characteristic he/she is willing to "pay up" for.

The price of an MBS pool is influenced by prepayment speed, usually measured in units of CPR or PSA. When a mortgage refinances or the borrower prepays during the month, the prepayment measurement increases.

If the buyer acquired a pool at a premium (>100), as is common for higher coupons then they are at risk for prepayment. If the purchase price was 105, the investor loses 5 cents for every dollar that's prepaid, possibly significantly decreasing the yield. This is likely to happen as holders of higher-coupon MBS have good incentive to refinance.

Conversely, it may be advantageous to the bondholder for the borrower to prepay if the low-coupon MBS pool was bought at a discount. This is due to the fact that when the borrower pays back the mortgage he does so at "par". So if the investor bought a bond at 95 cents on the dollar, as the borrower prepays he gets the full dollar back and his yield increases. This is unlikely to happen as holders of low-coupon MBS have very little incentive to refinance.

The price of an MBS pool is also influenced by the loan balance. Common specifications for MBS pools are loan amount ranges that each mortgage in the pool must pass. Typically, high premium (high coupon) MBS backed by mortgages no larger than 85k in original loan balance command the largest pay-ups. Even though the borrower is paying an above market yield, they are dissuaded to refinance a small loan balance due to the high fixed cost involved.

Low Loan Balance: < 85k

Mid Loan Balance: Between 85k - 110k

High Loan Balance: Between 110k - 150k

Super High Loan Balance: Between 150k - 175k

TBA: > 175k

The plurality of factors makes it difficult to calculate the value of an MBS security. Quite often, market participants do not concur resulting in large differences in quoted prices for the same instrument. Practitioners constantly try to improve prepayment models and hope to measure values for input variables implied by the market. Varying liquidity premiums for related instruments as well as changing liquidity over time, makes this a devilishly difficult task.

See also

- Commercial mortgage-backed security

- Dollar roll

- Residential mortgage-backed security

- Collateralized mortgage obligation

- Securitization

- Structured finance

- Subprime mortgage crisis

- United States housing bubble

- Countrywide Financial

- New Century Financial

References

- ↑ "Mortgage-Backed securities". U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. http://www.sec.gov/answers/mortgagesecurities.htm.

- ↑ "Risk Glossary". http://www.riskglossary.com/link/mortgage_backed_security.htm.

- ↑ Fabozzi, Frank J.; Modigliani, Franco (1992), Mortgage and Mortgage-backed Securities Markets, Harvard Business School Press, pp. 18–19, ISBN 0-87584-322-0

- ↑ Fabozzi, Frank J.; Modigliani, Franco (1992), Mortgage and Mortgage-backed Securities Markets, Harvard Business School Press, p. 19, ISBN 0-87584-322-0

- ↑ Fabozzi, Frank J.; Modigliani, Franco (1992), Mortgage and Mortgage-backed Securities Markets, Harvard Business School Press, pp. 19–20, ISBN 0-87584-322-0

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Fabozzi, Frank J.; Modigliani, Franco (1992), Mortgage and Mortgage-backed Securities Markets, Harvard Business School Press, p. 20, ISBN 0-87584-322-0

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Fabozzi, Frank J.; Modigliani, Franco (1992), Mortgage and Mortgage-backed Securities Markets, Harvard Business School Press, p. 21, ISBN 0-87584-322-0

- ↑ Fabozzi, Frank J.; Modigliani, Franco (1992), Mortgage and Mortgage-backed Securities Markets, Harvard Business School Press, p. 23, ISBN 0-87584-322-0

- ↑ Fabozzi, Frank J.; Modigliani, Franco (1992), Mortgage and Mortgage-backed Securities Markets, Harvard Business School Press, p. 25, ISBN 0-87584-322-0

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Fabozzi, Frank J.; Modigliani, Franco (1992), Mortgage and Mortgage-backed Securities Markets, Harvard Business School Press, p. 31, ISBN 0-87584-322-0

- ↑ Fabozzi, Frank J.; Modigliani, Franco (1992), Mortgage and Mortgage-backed Securities Markets, Harvard Business School Press, pp. 33–34, ISBN 0-87584-322-0

- ↑ Fabozzi, Frank J.; Modigliani, Franco (1992), Mortgage and Mortgage-backed Securities Markets, Harvard Business School Press, p. 26, ISBN 0-87584-322-0

- ↑ Joseph G. Haubrich, Derivative Mechanics: The CMO, ECONOMIC COMMENTARY, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, Issue Q I, pages 13-19, (1995).

- ↑ Keith L. Krasney, "Legal Structure of Net Interest Margin Securities", The Journal of Structured Finance, Spring 2007, Vol. 13, No. 1: pp. 54-59, DOI: 10.3905/jsf.2007.684867

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Federal Reserve Statistical Release

- ↑ Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association Statistical Release

- ↑ Ross, Stephen A., et al. (2004). Essentials of Corporate Finance, Fourth Edition. McGraw-Hill/Irwin. pp. 158,186. ISBN 0-07-251076-5.

External links

- FannieMae's Mortgage-Backed Securities page, including an MBS locator by CUSIP, Pool or Trust Number

- Vink, Dennis and Thibeault, André (2008). "ABS, MBS and CDO Compared: An Empirical Analysis" The Journal of Structured Finance

- More Mortgage Madness by Kai Wright, The Nation, April 29, 2009

- MBS Basics by Mortgage News Daily, MBS Commentary

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||